I pay attention when another author’s book captivates my attention. I’ll analyze the detail, pace, prose, and voice, and try to figure out what exactly it was that grabbed me. (Sometimes the opposite is true: I’ll read a terrible book and obsess over how it became a NYT bestseller, and then sink into a funk and go back to reading biographies of comedians).

But, just as often, I’ll analyze an intriguing movie or television show to help my own suspense writing. Why did that show hook me? What about that movie made me hold my breath?

With that premise in mind, here are five big-and-little-screen examples of elevating suspense above the ordinary, and how they’ve helped me with my own storytelling.

Breaking Bad (Pilot)

This is a classic what-the-hell-is-happening episode, with the viewer thrown into instant chaos. A man wearing nothing but his underwear and a gas mask frantically tries to control his RV as he speeds through the desert. Cut to bodies on the floor, sliding back and forth. RV careens into a ditch, driver gets out. He’s middle-aged, scared, and somehow relatable. There’s an instant sense he’s not a bad guy, so we decide—for no real reason—to root for him.

As he records a farewell to his wife and son with a video camera, we hear the approach of sirens.

Are you kidding me? Watch the first few minutes and tell me you don’t care what happens next. I won’t believe you if you do.

How this helps my writing: It teaches me to throw my reader immediately into the fire. No set up—just straight to the flames. The key is keeping the chaos simple, or the reader might get too confused to care.

Jaws (The Indianapolis Speech)

This is the epitome of a riveting monologue. Slow, steady, controlled, accented by the soft creaking of boat rocking on gentle waters. Nighttime. Robert Shaw, as Quint, tells his two boat mates a horrifying story about sharks. But listen to the words. The casual asides. Watch his face. The slight grins. His pauses as he sips his drink. All those little motions and breaks make the impact sentences punch you in the gut. “When he comes at you, he doesn’t seem to be living. Until he bites you, and those black eyes roll over white.”

How this helps my writing: I remind myself the key to tension is often the lack of anything big happening. Keep it subtle. In this case, it’s just a guy talking, telling a soft-voiced story. But the impact words (bite, scream, blood) fall into a poetic rhythm, dropping sporadically at the beginning of the speech, and then falling like rain as the story reaches its climax. Robert Shaw hardly talks above a whisper in this scene. He doesn’t have to.

Fargo, Season 1 (Pilot) – There Be Dragons scene

The movie Fargo is a gem and a study unto itself, but season one of the eponymous television series is a treasure trove for writers. Case in point: toward the end of the pilot episode, Lorne Malvo (Billy Bob Thornton) is pulled over at night for speeding by small-town cop Gus Grimly (Colin Hanks). Hanks’s aw-shucks, mid-west attitude is beautifully contrasted by Thonton’s dead-eyed, emotionless delivery. When Hanks asks for his license and registration, Thornton counters with a chillingly honest assessment of what will happen next. It’s tense and original, with even a reference to old-world maps using there be dragons to indicate unexplored territories.

How this helps my writing: This teaches me that a particularly scary character is one who is understated and true to his or her twisted beliefs. Thornton’s only weapons in this scene are his words and his confidence, both of which are used to full effect. I try to make my bad guy or girl believe fully in what they are doing, then have them do their horrible deeds with a detached calm. Now that’s scary. See also: Chigurh (No County for Old Men).

Shawshank Redemption

The whole fucking thing. Watch the whole thing, then watch it again. Then read the story, then watch the movie again. Go. Now.

How this helps my writing: There is no greater sympathetic character than Andy Dufresne. And it’s not just because he’s innocent, but because every person watching or reading Shawshank pictures themselves in Dufresne’s shoes. His story is ultimately one long game of what would you do? If I can make my reader exist in my protagonist’s shoes for the whole story, it’s hard to falter.

Reservoir Dogs (Tipping Scene)

There is no substitute for clever writing, and mining small, humorous nuggets in a scene can vastly bolster a dramatic overall storyline. This has to be done very carefully; if not done well, it will appear as if the writer is trying too hard. Watch the scene where Mr. Pink (Steve Buscemi) dines with his would-be heist-mates and unleashes a barrage about why he doesn’t believe in tipping. It’s short, unexpected, and funny; moreover, it offers a very humanistic insight on a character we know very little about. Even better? The hatred Mr. Pink’s position brings out in the other criminals. While the monologue paints Mr. Pink in a Libertarian shade, it elevates the other crooks to a Robin Hood level. Sure, they’ll steal diamonds from the rich, but God forbid you stiff a waitress her tip.

How this helps my writing: Quirky and funny in small doses will make any work of suspense that much more memorable. Moreover, it keeps the reader just a little off-balance, making scenes of tension and violence all the more jarring. But it’s important I don’t overdo it, or I’ll take the reader too far out of the story to care.

What I’m Watching

After Life, Netflix (2019). I’m mostly a fan of Ricky Gervais, and I think he’s one of the smartest comedic writers out there. The Office and Extras, in particular, are PhD-levels studies in awkward moments. So I was excited to see a new dark-comedy short-series created, directed, and starring Gervais. After Life following the life of Tony, a middle-aged small-town British journalist who has abandoned all joy in life after losing his wife of 25 years to cancer. His joylessness has resulted in his “superpower,” which is his new ability to say and do whatever he wants without regard to anyone else.

In essence, this show is Gervais wanting to unleash comic brutality but needing a shield of empathy to hide behind. The brutality is fairly enjoyable, but Tony works to hard to remind everyone at frequent turns that he’s allowed to do so because his wife is dead. It gets old pretty quickly, and that play for empathy becomes weighed down by flashback scenes with Tony and his wife, Lisa, who appear to have had a marriage too perfect to be believed.

Still, I watch. I watch because of Gervais, who has a delivery like no other, and has come up with constantly funny dialogue (dark, depressing, and overdone as it may be). Best line of the show is when Tony walks by a school yard and a chubby, uniformed grade-schooler shouts “pedo!” at him. Tony stops, peers through the fence at him, and says, ““I’m not a pedo and if I was, you’d be safe you tubby little ginger c***.”

Last Few Words I’ve Written

Apropos of nothing, I’m sharing a passage from my work-in-progress.

Photo of the Month

Bald eagles flying in tight formation, Erie, Colorado.

Update From My Kids

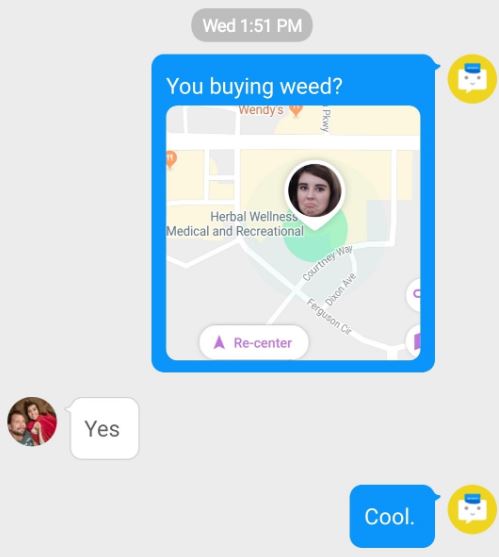

My kids and I use the Life360 app, which lets us see each other’s locations on a map. I don’t use it a lot, but now that my daughter is driving it is comforting to be able to check and see she’s made it to her destination. Unless that destination appears to be a marijuana dispensary.

Turns out, she was doing homework at a coffee shop right next to the dispensary. Right…..

Update From My Cat

Part one in a series where my demonic cat chases my children. First up is Ili (click picture to watch video).

What’s in My Backyard?

Nothing! For the last month I’ve seen a squirrel, a rabbit, and a stray cat. That’s it. I need to figure out how to lure more interesting animals back into that area (in South Park, they used a pentagram).